- The American Epistemology Institute

- Posts

- America's Metaphysical Axiom

America's Metaphysical Axiom

One Human Nature and the Limits of Law

Abstract

This article examines the metaphysical foundation of American law as articulated in the Declaration of Independence: that all humans share one nature and are equal before a law higher than the state. Contrasting this foundational axiom with later statutory exclusions—specifically the racial bar in the Naturalization Act of 1790—it applies classical natural law reasoning and the principle of non-contradiction to show that such exclusions are not merely unfortunate "determinations," but unjust laws that contradict America's founding metaphysic. Clarity on metaphysical equality is essential to prevent both historical injustice and modern misreadings of "equality."

Introduction

America's political order rests on a profound metaphysical claim (a foundational truth about the nature of reality). The Declaration of Independence sets forth an axiom (a self-evident principle): "all men are created equal," possessing natural rights endowed by their Creator. This universal principle grounds law above the will of rulers and establishes a standard for justice that subsequent acts of legislation must respect. However, America's legal history contains clear departures from this standard. Most starkly, the Naturalization Act of 1790 restricted citizenship to "free white persons," a statutory determination that cannot be reconciled with the founding metaphysical universal. This article uses classical natural law reasoning (the philosophical method that derives moral and legal principles from human nature and reason) to explain why such contradictions matter, how they arise, and how metaphysical clarity protects against both past and present errors.

I. The Metaphysical Axiom: Equality by Nature

QUOTE:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal … endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights …" (Declaration of Independence, 1776, para. 2).

CLAIM:

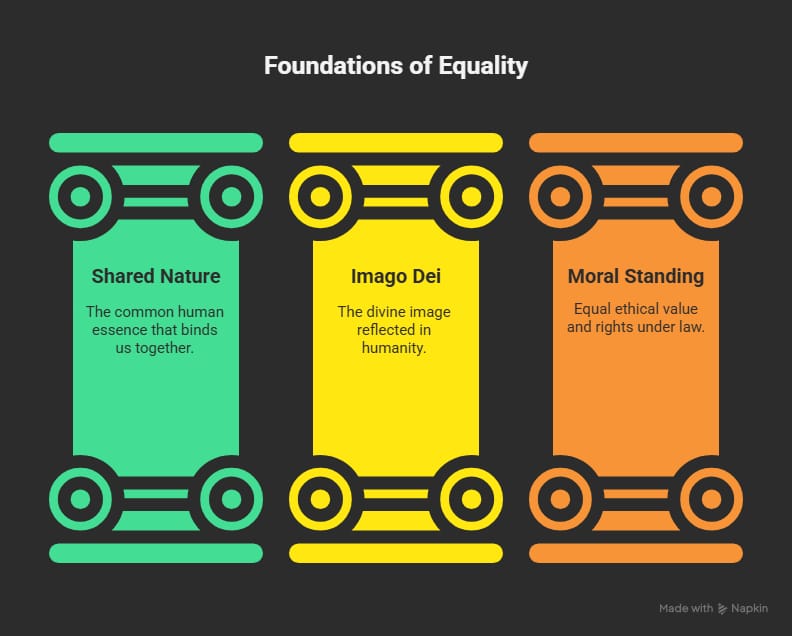

The founding axiom is ontological equality (equality rooted in the fundamental nature of being), grounded in our shared nature and the imago Dei (the image of God in humanity). Here, "equality" means equal moral standing and jurisdiction under law, not sameness of talents or outcomes.

ANALYSIS:

The Declaration's "self-evident" truth coheres with Aristotelian-Thomist first principles (the philosophical synthesis of Aristotle's logic with Thomas Aquinas's Christian philosophy) and Scottish common-sense realism (the philosophical school that trusted ordinary human reasoning to discover moral truths). To be human is to possess a rational nature - the rational framework of humans characterized by the intellect (Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I q.79 a.1-3) and the will (ST I q.82 a.1 & a.4). This framework allows man the ability to know Truth and choose the Good. As such, humans possess a dignity that law must acknowledge. This universal (a principle that applies to all cases within its scope)—that all persons are equal due to their possession of the powers of intellect and will—fixes the standard against which all future laws are measured (ST I–II q.95 a.2).

For a fuller exposition of how Aristotelian-Thomist realism and Scottish Common Sense philosophy provided the metaphysical foundations for American political thought—in contrast to Lockean nominalism (the philosophical view that universal concepts are merely names rather than real features of reality)—see the American Epistemology Institute's article titled, "A Fixed Star or Shifting Sands: Reclaiming America's Realist Foundations," American Epistemology Institute (June, 2025).

Sidebar: Defining Equality

Equality of nature (axiom): one human essence, equal moral standing under the Creator, equal jurisdiction of law.

Equality before law: equal protection and due process for all persons sharing that nature.

Not equality of outcome or ability: outcomes and talents vary by contingent causes; the axiom promises equal standing, not sameness of results.

II. The Statutory Contradiction: The 1790 Naturalization Act

Given this metaphysical foundation—that all humans possess rational nature and therefore equal dignity—how do we account for America's early legal departures from its own axiom? The most glaring example emerges just fourteen years after the Declaration.

QUOTE:

"Any alien, being a free white person, may be admitted to become a citizen …" (Naturalization Act of 1790).

CLAIM:

Congress enacted a racial prerequisite that directly denies the universal scope established by the founding axiom.

ANALYSIS:

When human laws apply universal principles to specific circumstances, they must remain faithful to those principles' core meaning (ST I–II q.95 a.2). The 1790 Act violated this requirement: by limiting naturalization to "free white persons," it based legal distinctions on an accidental characteristic (a non-essential trait that doesn't define what something fundamentally is)—race—rather than the essential human capacity for reason and moral choice. This kind of specification corrupts the law's purpose.

The Militia Act of 1792 enrolled "every free able-bodied white male citizen," reinforcing the same error in another domain.

This contradiction was not accidental. It reflected a competing philosophical framework that would undermine America's realist foundations.

III. Continental Enlightenment Intrusion: When Reason Serves Prejudice

How did American legislators, working within a generation of the Declaration's universal axiom, justify such blatant contradictions? The answer lies in the competing influence of Continental Enlightenment thought, which some founders attempted to merge with America's Aristotelian-Thomist and Scottish realist foundations—a synthesis that was metaphysically contradictory due to the law of non-contradiction. A thing cannot both be and not be at the same time. This reveals the contradiction in merging two opposing approaches to human nature. One uses reason to discover the essential equality of all humans as rational beings in the imago Dei. The other uses reason to construct hierarchies that divide humans by accidental characteristics.

QUOTES:

"The negroes of Africa have by nature no feeling that rises above the trifling" (Kant, Observations on the Beautiful and Sublime, 1764)

"I am apt to suspect the negroes ... to be naturally inferior to the whites" (Hume, "Of National Characters," 1748).

CLAIM:

The 1790 Act's racial exclusion reflects Continental Enlightenment assumptions about human hierarchy that contradicted America's Aristotelian-Thomist foundations.

ANALYSIS:

While America's founding drew primarily from Aristotelian-Thomist metaphysics and Scottish common-sense realism, Continental Enlightenment thought (the philosophical movement centered in France and Germany that emphasized systematic reason over traditional authority)—particularly from figures like Hume and Kant—compromised American legal reasoning with devastating consequences. These philosophers, despite championing "reason," used rationalistic methodology (the approach that constructs elaborate theoretical systems that may override common-sense observations) to construct elaborate justifications for racial hierarchy that directly contradicted the metaphysical axiom of equal human nature.

The Continental approach differed fundamentally from American realism in its method and conclusions:

Scottish Realist Method: Reason discovers universal truths about human nature through common sense and natural law principles. All humans possess rational nature; therefore, all possess equal dignity.

Continental Method: Reason constructs systematic theories that may override common-sense observations about human equality. Philosophical systems justify excluding entire groups from full human consideration.

The 1790 Act represents this Continental contamination of American law. Rather than faithfully determining the universal of human equality, Congress employed rationalistic prejudice to create a legal fiction—that race constitutes an essential difference in human nature. This marked a departure from the founding metaphysic toward what would later enable more radical departures from subsidiarity and constitutional order.

The Subsidiarity Compromise:

By accepting Continental assumptions about human hierarchy, American law opened a crack in its metaphysical foundation. If race could determine essential human worth, then other systematic revisions of natural equality became theoretically possible. This compromise created the intellectual precedent that later radicals would exploit to justify overturning federalism (the division of power between national and state governments), local governance, and constitutional limits in the name of "correcting" America's founding principles. We will explore this further in future papers.

But how do we distinguish between legitimate legal determinations and such perversions of law? Classical natural law theory provides the answer.

IV. The Principle of Non-Contradiction: Law's Two-Level Structure

QUOTE:

"Human law is derived from the natural law either by way of conclusion or by way of determination of certain generalities” (applying universal principles to specific circumstances) (Aquinas, ST I–II q.95 a.2). However, when human law contradicts natural law, it becomes illegitimate: "An unjust law is not law, but a perversion of law" (Aquinas, ST I–II q.96 a.4).

CLAIM:

Positive law (human-made law that applies natural law principles to specific circumstances) is legitimate only when it faithfully specifies the universal; it cannot rightly declare any class outside the protection of equal standing under the law.

ANALYSIS:

America's legal hierarchy operates on two levels:

Universal: the metaphysical axiom (equality by nature).

Specification: prudential laws that determine how universals apply (residency, allegiance, age, venue, oath).

If a determination contradicts the universal—for example, by legislating a racial essence—it becomes unjust even if procedurally enacted. In realist terms, the axiom of equality tests the law's justice, not the reverse. Aquinas names such enactments "acts of violence rather than laws" (ST I–II q.96 a.4).

This framework provides clear criteria for evaluating any law's legitimacy.

V. Objections and Replies

Objection 1: "The Declaration is not law."

Reply: The Declaration states the nation's metaphysical axioms that norm legislation. Statutes, as positive law, sit beneath and are measured by these higher truths. (Text at National Archives link above.)

Objection 2: "But 'all men' excluded groups at the time."

Reply: That historical gap shows the distance between first principles (axiom) and imperfect legislative practice. The axiom itself condemns those exclusions.

Objection 3: "Equality means sameness of outcomes."

Reply: No. The axiom is ontological and juridical equality—shared nature and equal legal standing. Outcomes and talents rightly vary; prudential laws may distinguish non-essential factors (age, allegiance), but not supposed racial essence.

These objections reveal the stakes of maintaining clarity about America's founding principles.

VI. Conclusion

The Declaration of Independence enshrines a universal axiom: all humans share one nature and equal moral standing under law. Laws that contradict this standard—such as the 1790 Naturalization Act's racial exclusion—are not just wrong by today's lights, but unjust by the very logic of America's founding. Clarity about first principles and their lawful determination is the only path to coherence and lasting justice in American civic life.

References

Declaration of Independence. (1776). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

Naturalization Act of 1790 (1790). https://immigrationhistory.org/item/1790-nationality-act/

Militia Act of 1792 (1792). https://www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-source-collections/primary-source-collections/article/militia-act-of-1792

Aquinas, T. (1273). Summa Theologiae. https://www.newadvent.org/summa/

Hume, D. (1748). "Of National Characters." In Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary. https://davidhume.org/texts/empl1/nc

Kant, I. (1764). Observations on the Beautiful and Sublime. https://books.google.com/books/about/Observations_on_the_Feeling_of_the_Beaut.html?id=K-9G31HUQEwC

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Aquinas' Moral, Political, and Legal Philosophy." https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aquinas-moral-political