- The American Epistemology Institute

- Posts

- A Fixed Star or Shifting Sands: Reclaiming America's Realist Foundations

A Fixed Star or Shifting Sands: Reclaiming America's Realist Foundations

Why Aristotle, Aquinas, and Scottish Common Sense Realism, Not Locke's Nominalism, Defined Early American Political Philosophy

Abstract

This white paper explores the foundational metaphysical and epistemological principles that undergirded early American political philosophy. Drawing from Aristotle’s teleological realism, Aquinas’s Christian natural law tradition, and the Scottish Common Sense Realism of Thomas Reid, it contrasts these with the nominalist metaphysics of John Locke. The paper argues that while Locke’s influence is often overstated, it was the metaphysical realism of Reid and legal naturalism of James Wilson that more accurately reflect the Original American Epistemology (OAE). The discussion highlights the incompatibility between Locke’s constructivist social contract theory and the fixed moral ontology espoused by Reid, Aquinas, and Wilson. In doing so, it calls for a return to the realist foundations upon which the American regime was initially conceived.

Realist Metaphysical Foundations of American Philosophy

Originally, American political and philosophical thought rested on a realist framework inherited from Aristotle, refined by Thomas Aquinas, and bolstered by Thomas Reid and James Wilson. Aristotle taught that all beings fit into a natural order or hierarchy of being, each with its own nature and purpose (an acorn will grow into nothing else but an oak tree). He described nature as a graded scale: all living things share the nutritive principle (plants), many add perception and movement (animals), and only humans possess rationality (the intellectual telos) (Aristotle, 1998). In his Metaphysics, he insisted that reality is knowable through its natures: "substance" (ousia) is the metaphysical bedrock on which all else is built. Thus Aristotle grounded knowledge and ethics in an objective world ordered by natural forms and teleological ends (Aristotle, 1998). In other words, because reality has an order and is not random, reality is knowable and categorizable (and runs contrary to nominalism). Furthermore, since reality is knowable and able to be categorized, it can also be said that the objects in reality have a purpose or telos.

Thomas Aquinas built on Aristotle’s hierarchy by Christianizing it. In Thomism, every level of being has its proper form and soul, ordered toward higher ends. Aquinas famously charts a “ladder of existence”: non‑living matter underlies life; plant life (with a vegetative soul) grows and reproduces; animal life (with sensitive souls) can move and feel; human life (with a rational soul) understands and chooses; above humans are the spiritual angels; and above all stands God as the Unmoved Mover and ultimate source of intelligible order (Aquinas, 1947). In this view, God ordained the natural order and engraved basic moral principles on human nature. Aquinas saw nature as holistic and integrated, where higher forms “produce in a more interior way” precisely because of their souls. In short, Aquinas preserved Aristotle’s realism—natures, forms, and final causes—adding a divine tier that embeds beings in a purposeful cosmos.

Scottish Common Sense Realism and the Aristotelian Tradition

In the 18th century, Scottish thinkers like Thomas Reid revived and extended this realist perspective in epistemology and ethics. Reid’s Common Sense Realism held that certain first principles are innate and self‑evident; we are “wired by nature” to know them (Reid, 1764/1997). Reid argued that some truths (e.g. “the external world exists,” “other people have minds,” basic moral duties) are so plain that all rational people accept them by common sense. These principles form the foundation of knowledge and morality. Americans rapidly embraced Reid’s ideas: schools taught students that sense experience, guided by these inborn truths, can indeed yield secure knowledge (Reid, 1764/1997).

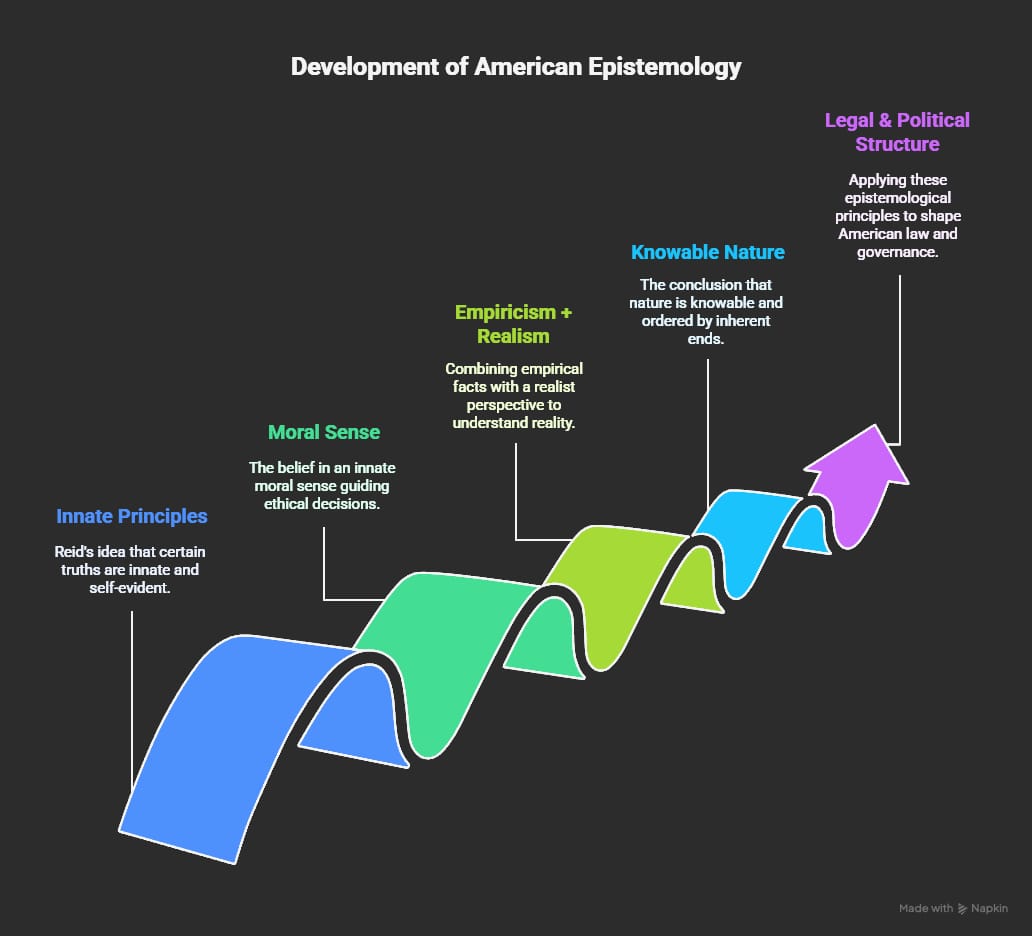

In effect, Scottish Realism aligned with the Aristotelian-Thomistic order by insisting that human nature itself reveals an intelligible, ordered universe and moral law. Reid's epistemological grounding in realism became a foundational element of what would emerge as the Original American Epistemology (OAE).

First Principles are Innate: Reid held that certain “first principles” (e.g., existence of God or the external world) are “wired into us by nature” and are universally and objectively true (Reid, 1764/1997).

Moral Sense: He believed a moral sense is also innate, implying an objective natural law within us. Americans like President Jefferson and justice James Wilson saw this as supporting natural law and rights (Wilson, 1791/1984).

Empiricism + Realism: Scottish thinkers maintained Newtonian science (the Regulae Philosophandi) while rejecting radical skepticism. They insisted empirical facts fit into an intelligible order and that our common-sense ideas are reliable markers of reality (Reid, 1764/1997).

Thus Scottish Common Sense Realism, rooted in Aristotelian-Thomistic ideas, helped forge a worldview in early America that nature is knowable and normed by inherent ends - that is to say that human nature has an objective order based on the teleology inherent in man. James Wilson carried this epistemological realism directly into the legal and political structure of the early United States, affirming that the Constitution and American law must be grounded in universal truths accessible by reason and the moral sense. Together, Reid and Wilson shaped the metaphysical and epistemological DNA of the American founding—one that assumed reality is both knowable and normatively structured.

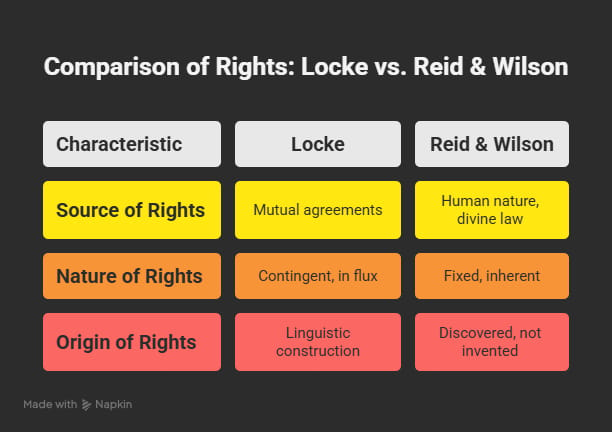

This stands in stark contrast to John Locke’s nominalist metaphysics. Locke denied the real existence of universals, treating concepts such as “rights” or “justice” as linguistic constructions derived from sensory experience and generalized through abstraction (Locke, 1690/1996). Because these abstractions are not grounded in real natures but in names, Locke's view places rights in the realm of designation and consent, not essence. In Locke’s social contract theory, rights emerge not from our nature or divine design but from mutual agreements and practical arrangements to avoid conflict and protect property (Locke, 1689/1988).

In metaphysical terms, this means that rights are not fixed or inherent; they are contingent and in flux, dependent upon prevailing definitions and political agreements. This is fundamentally incoherent with the American realist tradition. For Reid and Wilson, rights are real because they are grounded in human nature as created in the Imago Dei—bearing reason, will, and moral responsibility. Natural rights (like truth) are not invented; they are discovered. They are participations in eternal truths, not contractual conveniences. Reid’s innate moral sense and Wilson’s appeal to divine natural law assert that rights derive from what man is, not from what man wants or agrees to. Therefore, Locke’s epistemology and metaphysics cannot sustain the moral and legal architecture built by those who adhered to the OAE.

The tension is a concept we will revisit. Simply put, realism and anti-realism don’t mix. Logically speaking, a system attempting to incorporate both effectively collapses into anti-realism. This collapse can be understood through the lens of Aristotle's Principle of Non-Contradiction, which asserts that a thing cannot simultaneously be and not be, or possess and not possess the same quality, in the same respect and at the same time. If something is truly real, its reality and fundamental properties must not depend on our minds for its existence. Once mind-dependence, construction, or epistemic limitation is introduced as a foundational element within the system itself to account for certain aspects of reality or knowledge, it tends to spread. It becomes difficult to maintain a boundary between the "mind-independent" and "mind-dependent" aspects, as our only access to any reality is through the very cognitive or linguistic filters that anti-realism highlights. In this way, the anti-realist current neutralizes the realist one, leading to an overall system that is effectively anti-realist in its implications for knowledge and existence. The anti-realist, in this scenario, has essentially set the terms of the game. If you admit that any part of reality is constituted by our minds/language/social practices, and you also accept that our access to all reality is mediated by these same constructs, then the claim of pure mind-independence becomes extremely difficult to maintain or verify from within the system. The 'realist' part becomes a belief that can't be demonstrably accessed or distinguished from the 'anti-realist' part, rendering the overall operational framework effectively anti-realist and in direct contradiction to the realism inherent in America's metaphysical makeup at its founding. We'll investigate these realism-divergences in future papers.

References

Aristotle. (1998). Metaphysics (H. Lawson-Tancred, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published ca. 350 B.C.E.)

Aquinas, T. (1947). Summa Theologiae (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). Benziger Bros.

Locke, J. (1689/1988). Two treatises of government (P. Laslett, Ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Locke, J. (1690/1996). An essay concerning human understanding (P. H. Nidditch, Ed.). Oxford University Press.

Reid, T. (1764/1997). An inquiry into the human mind on the principles of common sense (D. R. Brookes, Ed.). Pennsylvania State University Press.

Wilson, J. (1791/1984). Lectures on law. In J. M. Becker (Ed.), Collected works of James Wilson (Vol. 1). Liberty Fund.