- The American Epistemology Institute

- Posts

- Two Enlightenment Traditions: Scottish Realism vs. Contract Liberalism at the American Founding

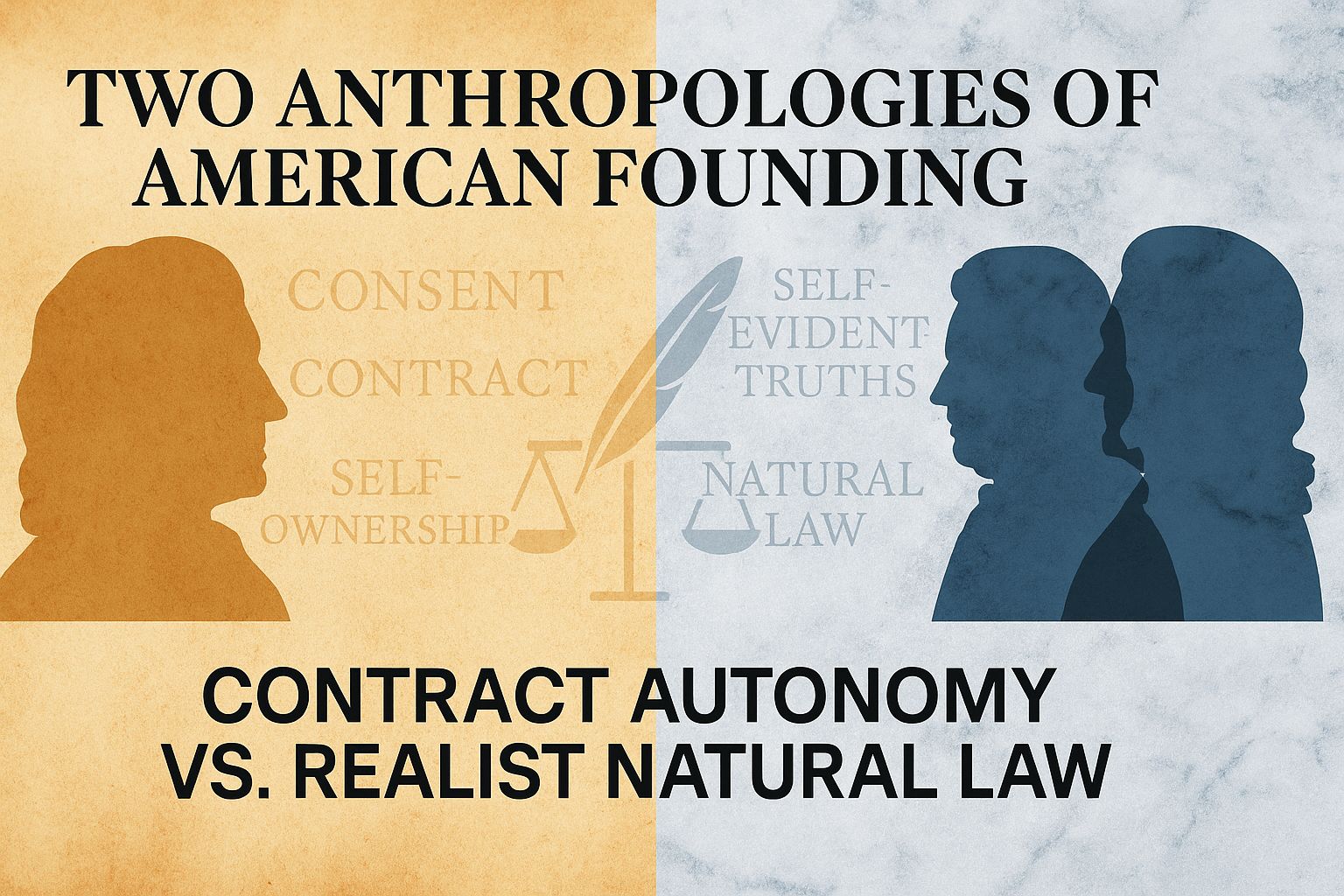

Two Enlightenment Traditions: Scottish Realism vs. Contract Liberalism at the American Founding

Incompatible Anthropologies and the Path to Constitutional Coherence

Abstract

The American Founding drew on two Enlightenment traditions. A broad Continental/English current—anchored by Locke and later read through autonomy-centric lenses—supplied consent and contract grammar and, in later interpretations, a path for exclusionary positive law (e.g., determining who counts as a party to the compact) (Locke, 1690/1988). The Scottish Common Sense stream (Reid, Wilson, Witherspoon) grounded knowledge and law in realist first principles and theistic natural law (Reid, 1785; Wilson, 1790–1791/2007; Witherspoon, 1776/2012). The Declaration’s universal claims align with this Scottish register; several early exclusions tracked with contractarian and proto-racial strands. This essay distinguishes the anthropologies, explains why realist founders could not fully resolve the tension in positive law, and proposes guardrails for realist coherence in interpretation.

Introduction

Founding-era incoherence stemmed from mixing incompatible anthropologies: (1) an Continental/English frame emphasizing consent, contract, and a metaphysically thin autonomy logic; and (2) a Scottish realist frame grounding equality in creation and natural law. Realists recognized the contradiction but lacked a durable coalition capable of imposing realist limits on early statutes and administrative practice (Wilson, 1790–1791/2007).

I. Two Anthropologies

A. The Continental frame: contract, structure, metaphysical thinness

The founding generation drew on two distinct Enlightenment traditions, each grounding political authority in fundamentally different metaphysical assumptions. Locke’s Second Treatise furnished the founding with a grammar of political authority: “no one can be… subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent” (II.VIII.95), coupled with the premise that an individual has “property in his own person” (II.V.27) (Locke, 1690/1988). The Declaration indicts royal abuses as breaches of consent; the Preamble’s “We the People” formalizes compact logic (Declaration of Independence, 1776; U.S. Const. pmbl.). This layer enabled a language of legitimacy, representation, and revocability of power.

Some structural borrowing proved especially durable. Montesquieu's separation of powers, often summarized as power checking power (XI.6), provided institutional machinery that proved adoptable even by future regimes rejecting his natural-law premises (Montesquieu, 1748/1989). The United States adopted this machinery alongside federalism and written constitutionalism, but hollowed it out over time.

The friction arises when contract grammar —itself metaphysically minimal rather than anti-realist— hardens into positive-law sovereignty, thus transforming law into declarations that actively contradict natural law rather than merely operating without explicit grounding in it. 'The people' is defined by statute alone; membership, personhood, and status are drawn without reference to natural law. Later interpreters extended Lockean themes toward expansive self-ownership and autonomy once detached from Locke's theistic assumptions. That move is interpretive and contingent (and is not Locke's explicit doctrine) yet it proved historically available within a contract-first framework whose metaphysical minimalism, while not inherently opposed to natural law, offered insufficient resistance to anti-realist readings (Locke, 1690/1988; Montesquieu, 1748/1989).

B. The Scottish Realist Frame

Reid rejected representationalism (the idea that we can only interact with mental representations of reality) and defended direct realism: perception places the mind in contact with the external world; certain first principles (the external world, causation, other minds) are rational bedrock that underwrite reasoning and moral judgment (Reid, 1785). On this basis, moral truths are not conventions but truths about reality accessible to reason.

Wilson translated this epistemology into jurisprudence. In his Lectures on Law, he argued that positive law is valid within, not above, natural law and that equality is ontological and knowable by reason. Legislative authority regulates means; it cannot redefine the nature of persons or nullify truths about rational agency (Wilson, 1790–1791/2007). Witherspoon integrated civic theology: liberty endures only where virtue, sustained by religion, forms citizens capable of self-rule (Witherspoon, 1776/2012). Read together, the Declaration’s grammar (“self-evident truths,” “created equal,” “endowed by their Creator,” “unalienable rights”) is realist anthropology, not policy fashion (Declaration of Independence, 1776).

II. Why the Contradiction Persisted

Coalitions and priorities. Realists such as Wilson argued from higher, natural law premises while operating within coalitions like the Federalists that prioritized national cohesion, institutional stability, and economic development. Despite Wilson's attempts to ground the Constitution's 'We the People' within natural law constraints, the formulation proved vulnerable to Rousseauian readings that claimed direct popular sovereignty (federal authority claimed directly from a national 'People' rather than delegated through mediating states)—a danger Anti-Federalists had warned against. The result? The practical agenda (securing credit, establishing revenue, consolidating peace) often eclipsed metaphysical consistency.

The synthesis assumption. Because the two traditions overlapped in institutional design (separation of powers, federalism), many founders seem to have assumed that they could be blended. The fault line surfaced when positive law diverged from natural law: contract logic and later 'race science' (itself anti-realist) supplied a justificatory path for exclusion such as the 1790 Naturalization; material interests entrenched it. Without organization and votes, philosophy yielded to politics.

Judicial and administrative drift. As administration matured, guidance and prudential accommodations often operated in the contractarian frame, especially where membership and status were treated as definable by statute alone. The Scottish realist constraint—that positive law cannot contradict truths about human nature—had fewer institutional guardians. By 1857, Chief Justice Taney could declare in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) that an entire class of rational beings fell outside 'the people' because the Founders had excluded them—a pure contractarian move treating positive law as constituting, rather than recognizing, personhood.

III. Methodological Guardrails (Realist)

Given these historical failures to maintain realist coherence, a disciplined methodology is essential. To align law with the Declaration’s premises, we can apply a three-part natural-law test to any legal distinction:

Identify a real difference in nature. The classification must correspond to an actual feature of reality, not a convention or stereotype.

Show functional relevance. The difference must matter to the function the law regulates.

Preserve essential equality. The law must recognize universal rational nature and intrinsic dignity (Aquinas, trans. 2006; Wilson, 1790–1791/2007).

Failure at any step renders the distinction metaphysically inadmissible. The test blocks false egalitarianism (ignoring real differences where relevant) and false hierarchy (elevating accidental traits to essentials).

IV. Prudential Devices That Fit Realism

Certain mechanisms serve realist ends without importing anti-realist premises:

Separation of powers / checks and balances. Power disciplines power (Montesquieu, 1748/1989).

Federalism. Jurisdictional allocation reduces consolidation while assuming natural-law limits on state and federal action (U.S. Const.).

Written constitutions. Public, durable, justiciable texts anchor higher-law claims in positive form.

Uniform naturalization procedures, juries, due process. Procedural safeguards align with natural-law justice by demanding reason-giving, evidence, and impartiality.

V. Objections and Clarifications

“Locke isn’t Continental.” Correct. “Continental/English” functions as a term marking the non-Scottish stream; the claim concerns metaphysical posture, not geography.

“Witherspoon and Wilson were slaveowners.” Yes; the argument concerns system coherence, not personal sanctity. Realist premises supply internal resources for critique.

“The Constitution does not say natural law binds positive law.” The claim is interpretive: the constitutional order presupposes the Declaration’s premises; Wilson and founding-era sources articulate that higher-law framework.

“This excludes non-theists.” No. Natural law is accessible to reason; theistic language frames but does not monopolize access to moral truths (Aquinas, trans. 2006; Wilson, 1790–1791/2007).

"You're just picking outcomes you like and calling them 'natural law.'"

The three-part test applies consistently across cases. It is a principled methodology, not ad hoc preference. Anyone committed to realist premises can apply it and reach the same conclusions.

VI. Conclusion

A coherent American metaphysic would keep prudent political machinery—separation of powers, federalism, written constitutionalism—while binding it to realist anthropology: equality of worth is Creator-grounded; rational nature is universal; statutes that contradict natural law are void in principle. The goal is harmonization: one coherent anthropology expressed through prudent institutions, enforcing the self-evident truth that all men are created equal.

References

Aquinas, T. (1265-1274/2006). Summa theologiae (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). New Advent. https://www.newadvent.org/summa/ (Original work written 1265-1274)

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857). https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/60/393

Locke, J. (1988). Two treatises of government (P. Laslett, Ed.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1690)

Montesquieu, C. de S. (1989). The spirit of the laws (A. M. Cohler, B. C. Miller, & H. S. Stone, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1748)

Naturalization Act of 1790, 1 Stat. 103 (1790). https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=001/llsl001.db&recNum=226

Reid, T. (1785). Essays on the intellectual powers of man. Online Library of Liberty. https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/reid-essays-on-the-intellectual-powers-of-man

U.S. Const. (1787). https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution

U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776). https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration

Wilson, J. (2007). Collected works of James Wilson (K. L. Hall & M. D. Hall, Eds.). Liberty Fund. https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/wilson-collected-works-of-james-wilson-2-vols (Original work published 1790-1791)

Witherspoon, J. (1776). The dominion of providence over the passions of men [Sermon]. Teaching American History. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-dominion-of-providence-over-the-passions-of-men/