- The American Epistemology Institute

- Posts

- The Fog of Power

The Fog of Power

How Managerial Ambiguity Breeds Centralized Control

Abstract

Managerial systems thrive on imprecision. In modern governance, as in corporate bureaucracy, murky language accelerates the accumulation of authority and shields its exercise from accountability. This dynamic is not new. The 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was designed precisely to counter the dangers of unbounded, undefined power—dangers the Founders recognized in the British Parliament’s claim to bind the colonies “in all cases whatsoever” (Parliament of Great Britain, 1766, para. II). When terms are left vague, authority flows upward, and decision-making becomes insulated from challenge. From the Revolutionary rejection of parliamentary overreach to the modern expansion of ambiguous categories like hate speech and gender, history shows that the fight for liberty is, in large part, a fight over clarity of terms.

Introduction

In every age, power has sought the shelter of ambiguity. From imperial proclamations to modern agency rulebooks, those who govern know that unclear terms make for pliable limits. Vagueness is not a flaw of the managerial order—it is a design feature. A word left undefined can stretch to fit the moment’s needs, shielding decision-makers from constraint and the public from recourse.

The American Revolution was fought against this very principle. Parliament’s Declaratory Act of 1766 asserted a right to bind the colonies “in all cases whatsoever,” a phrase so open-ended it could justify any intrusion. The framers answered with written constitutions and the 10th Amendment, which fixed powers in writing to bar exactly this kind of drift.

Yet in the modern West, the logic of the Declaratory Act has re-emerged—not in royal edicts, but in the elastic language of managerial policy. Terms like “hate speech” and “gender” have become endlessly expandable categories, eroding the boundaries the founders fought to secure. These conceptual fog banks serve the same purpose they did in 1766: concentrating authority in a central node, while obscuring the mechanisms of its growth.

I. The Manager’s Weapon: Ambiguity as Leverage

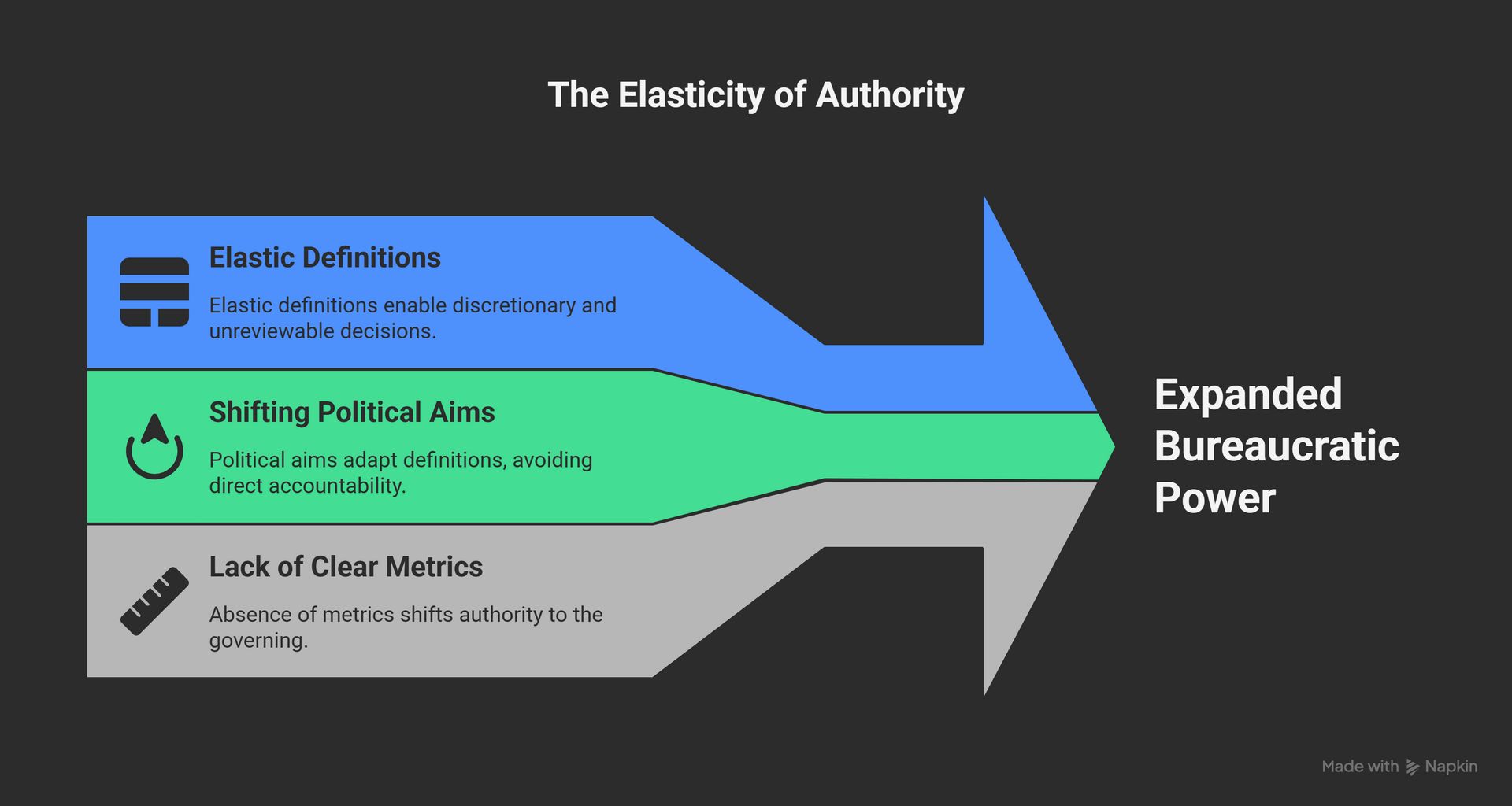

Modern managerial systems—from corporate HR departments to federal agencies—depend on elastic definitions. When policies use terms like “reasonable,” “appropriate,” or “necessary” without clear metrics, authority shifts from the governed to the governing. Decisions become discretionary, unreviewable, and insulated from concrete challenge.

Such elasticity allows bureaucratic actors to expand their remit without explicit mandate. By keeping definitions open-ended, power holders can adapt them to suit shifting political aims, all while avoiding direct accountability.

II. From Parliament’s Declaratory Act to Modern Speech Codes

The American Revolution was, at its root, a revolt against undefined authority. Parliament’s 1766 Declaratory Act claimed the “right… to bind the colonies and people of America…in all cases whatsoever” (Parliament of Great Britain, 1766, para. II). The language contained no limiting principle, making the scope of Parliament’s claim as broad as possible.

In the 21st century, a comparable dynamic appears in “hate speech” regulation. The term has no single, fixed definition across jurisdictions; it is fluid, subject to reinterpretation by the very bodies enforcing it. In Canada, the United Kingdom, and much of the European Union, laws restrict “hate speech” in ways that have expanded over time to include political dissent (Le Monde, 2024). In the United States, the First Amendment currently protects even offensive speech, but repeated legislative and activist efforts seek to carve out exceptions, mirroring trends abroad.

III. Brutus on the Dangers of Elastic Clauses

During the ratification debates, the Antifederalist writer Brutus warned that the Constitution’s necessary and proper clause could be extended to every possible case and thus grant Congress “absolute and uncontrollable power” (Brutus No. 1, 1787, para. 13). His concern was that without explicit and enforceable boundaries, the federal government could redefine its own authority in perpetuity.

Both the colonial resistance to the Declaratory Act and Antifederalist opposition to the Constitution recognized the same truth: once a clause or term is left elastic, liberty exists only at the discretion of those in power. This recognition is directly relevant to modern governance, where ambiguous categories like “gender” serve as policy levers for expanding regulatory reach.

As per the Nominalism: The belief that universals or general ideas are mere names without corresponding reality (e.g., male and female are only labels with no inherent correspondence with objective reality); only individual, particular things exist. → Destroys realism by denying that our concepts correspond to real categories.

IV. How Murkiness Undermines the 10th Amendment

The 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declares:

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

Its function was to set a hard boundary on federal jurisdiction. But in modern practice, managerial bodies bypass this boundary not by amending the Constitution, but by redefining its operative terms. Federal agencies stretch “interstate commerce” to include almost any economic activity. State and local governments rebrand mandates as “guidance,” evading legal review.

Two of the most potent examples are “hate speech” and “gender.”

Hate speech: Under current U.S. jurisprudence, the First Amendment protects even speech that others find hateful, so long as it does not cross into direct incitement of violence. Yet political and activist groups have sought to introduce exceptions, often modeled on foreign legislation. In Canada, the Criminal Code prohibits certain forms of “Wilful promotion of hatred” under sections 318–320 (Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46). In Scotland, according to the Hate Crime and Public Order Act, a "Hate Crime can be verbal or physical and can take place anywhere, including online." (Le Monde, 2024). Historically, such legislative models often influence U.S. policy indirectly. Here, the analog is “hate crime” statutes, which allow identical criminal acts to be prosecuted differently based on the perceived motive, introducing political subjectivity into sentencing.

Gender: Originally tied to language, “gender” became a separate, ambiguous category applied to people through the work of psychologist and self-described “sexologist” John Money, who oversaw the coerced “gender reassignment” of David Reimer after a botched circumcision, subjecting both Reimer twins to abusive sexualized experiments (Simply Psychology, 2025). Despite the exposure of this abuse, academia and policymakers adopted Money’s framework linking biological sex to “gender.”

This misapplied ambiguity opened an expansive, ill-defined zone for administrative and academic interpretation, enabling everything from pronoun enforcement to institutional restructuring. The redefinition of “gender” as a mutable identity category established a legal basis for expanding protected but nebulous classes, compelling specific language use, and reshaping institutional policy.

For example, in New York, the 2019 GENDA law (New York State Division of Human Rights, 2019) makes it unlawful in employment or housing interviews to ask about gender identity or expression, sex assigned at birth, medical history, or body parts—policies that build on precedents set by the “hate crime” framework.

The synergistic interplay between these two elastic terms is strategic: as “gender” grows more open-ended, “hate crime” statutes can expand into compelled speech and belief, enabling political authorities to treat dissent as criminal intent. This nominalist pairing dissolves the fixed limits the 10th Amendment was meant to safeguard. Keep in mind that these are just two examples of such murkiness.

V. Written Constitutions as Antidote to Vagueness

The American founding introduced a structural barrier against the growth of undefined power. Unlike Britain’s “unwritten constitution,” which relied on shifting precedent, the U.S. Constitution enumerated specific powers and reserved all others to the states or the people.

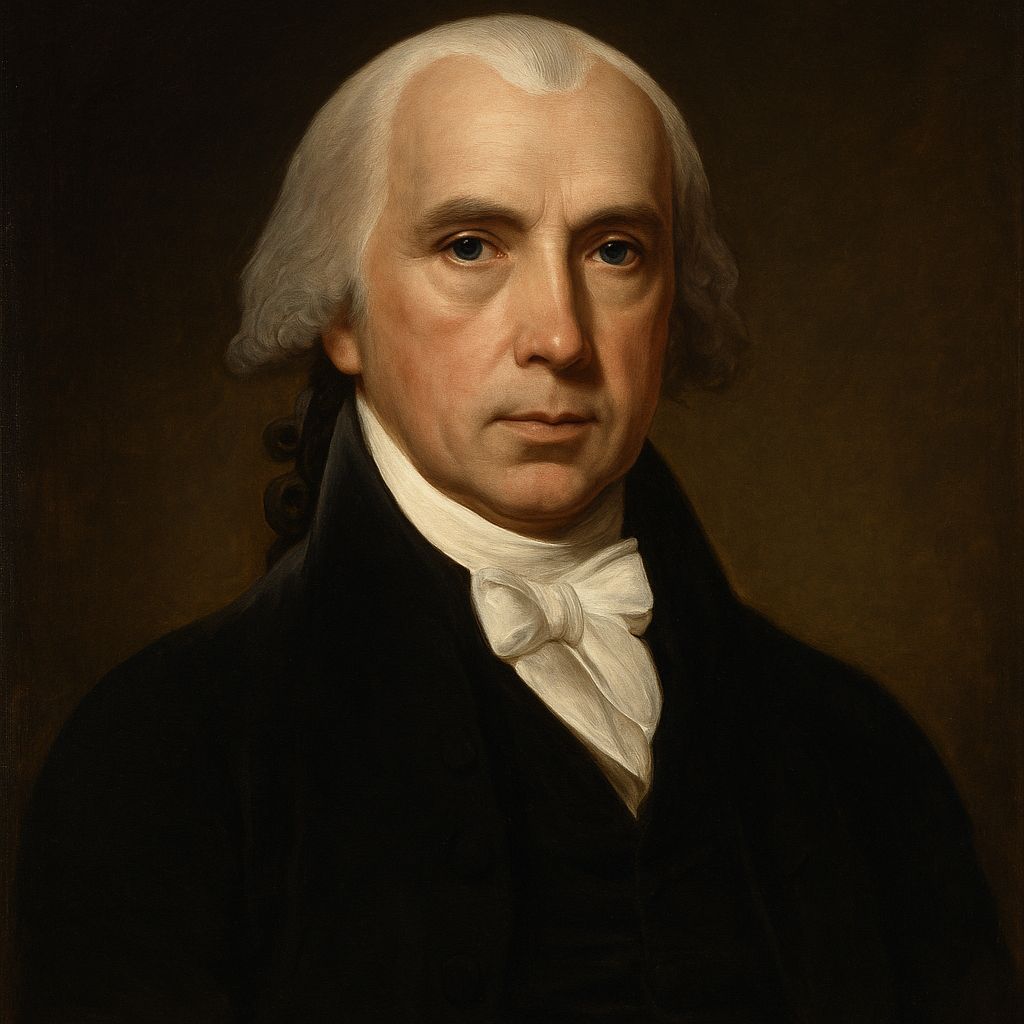

James Madison clarified this in The Federalist No. 45:

“The powers delegated by the proposed constitution to the federal government, are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the state governments are numerous and indefinite” (Madison, 1788, para. 9).

This design functioned as a safeguard, blocking the central government from claiming authority through vague implication. Anti-Federalists demanded the 10th Amendment to reinforce this limit in plain language. Their resistance drew directly from the colonial experience with British overreach, including the Declaratory Act’s assertion of unlimited power.

A written constitution operates as a linguistic defense. Its durability depends on the stability of the definitions it contains. When key terms are altered or obfuscated by those in authority, the intended constraints collapse in practice.

VI. The Acceleration Effect: Why Ambiguity Wins Quickly

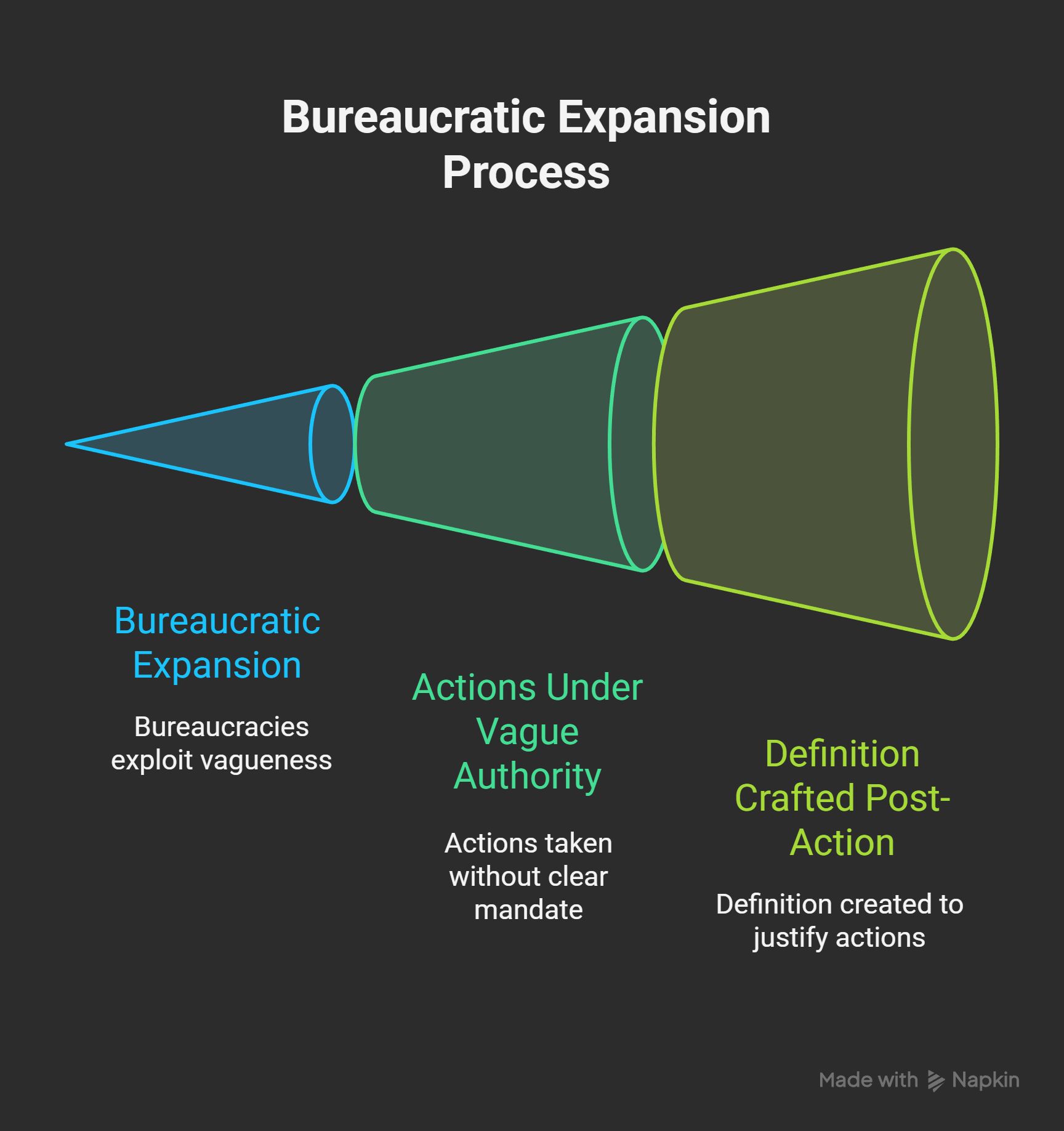

Power flows toward the least resistance. A well-defined legal term forces debate, invites litigation, and can be checked by precedent. An undefined term invites expansion and bureaucracies use this to their advantage: they act under vague authority, then fill in the meaning afterward, often only when challenged.

Indeterminacy invites bureaucratic abuse.

Ambiguity compresses the decision cycle. It allows managers—be they in government or corporate administration—to take action without pausing for explicit authorization. When the definition comes later, it is crafted to validate what has already been done. This reverses the constitutional order, in which powers are granted first and exercised second.

Vague terms also insulate decision-makers from accountability. If a policy outcome is unpopular, they can claim the term meant something else. If it is popular within their power base, they can codify the favorable interpretation. In either case, the governing body accrues more discretionary power, while the governed lose predictable, objective boundaries for action.

The effect compounds over time. Each successful expansion through ambiguity becomes the precedent for the next, until the original limits—whether in the 10th Amendment, the Bill of Rights, or statutory law—exist only in form, not in function.

Quote | Claim | Analysis |

|---|---|---|

“The powers delegated by the proposed constitution to the federal government, are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the state governments are numerous and indefinite.” (Madison, 1788, para. 9) | Federal power was meant to be narrowly bounded. | Managerial vagueness reverses this principle, allowing undefined powers to expand unchecked. |

“The powers of the general legislature extend to every case that is of the least importance — there is nothing valuable to human nature, nothing dear to freemen, but what is within its power.” (Brutus No. 1, 1787, para. 8) | Without clear limits, constitutional clauses can be exploited to grant unlimited authority. | Brutus identifies vagueness as the entry point for centralized despotism. |

“…to bind the colonies and people of America…in all cases whatsoever” (Parliament of Great Britain, 1766, para. II) | Parliament claimed unlimited authority over the colonies. | This undefined claim provoked revolutionary resistance and informed the 10th Amendment’s safeguards. |

VII. Demand Definition First

The Founders understood that liberty erodes when words lose their fixed meaning. The 10th Amendment imposed a structural demand: every power must be explicitly granted, and every grant must be bounded in scope.

Language is the first battleground of governance. A people who insist on precision in language preserve precision in law. Once that discipline is lost, constitutional protections become empty forms, waiting to be reinterpreted into irrelevance.

References

Brutus. (1787). Brutus No. 1. Retrieved from https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/brutus-i/

Criminal Code, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46, s. 319. (1985). Public incitement of hatred. Retrieved from https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/page-45.html#h-121176

John Money & the Reimer Twins. (n.d.). Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/david-reimer.html

Madison, J. (1788). The Federalist No. 45. Retrieved from https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0254

New York State Division of Human Rights. (2019). Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act (GENDA). Retrieved from https://dhr.ny.gov/genda

Parliament of Great Britain. (1766). Declaratory Act. Retrieved from https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/declaratory_act_1766.asp

Scotland’s new Hate Crime Law causes concern. (2024, April 1). Le Monde. Retrieved from https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/04/01/new-scottish-law-against-incitement-to-hatred-causes-great-concern_6667052_4.html

U.S. Constitution, amend. X. (1791). Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/bill-of-rights-transcript