- The American Epistemology Institute

- Posts

- American Metaphysics: A Realist Lexicon

American Metaphysics: A Realist Lexicon

Retrieving America’s First Principles from Constructivist and Nominalist Decline

Abstract

This white paper reclaims foundational American concepts from the distortions introduced by nominalism, pragmatism, and other anti-realist ideologies. Using a realist epistemology grounded in natural law, classical metaphysics, and the thought of figures like Aquinas and the American Founders, we construct a lexicon of terms such as rights, liberty, law, personhood, and justice. We contrast original metaphysical meanings with modern political distortions to illuminate the ontological and theological assumptions embedded in the American founding. Restoring these meanings is essential for recovering constitutional governance, civic virtue, and coherent public discourse.

The War on Meaning

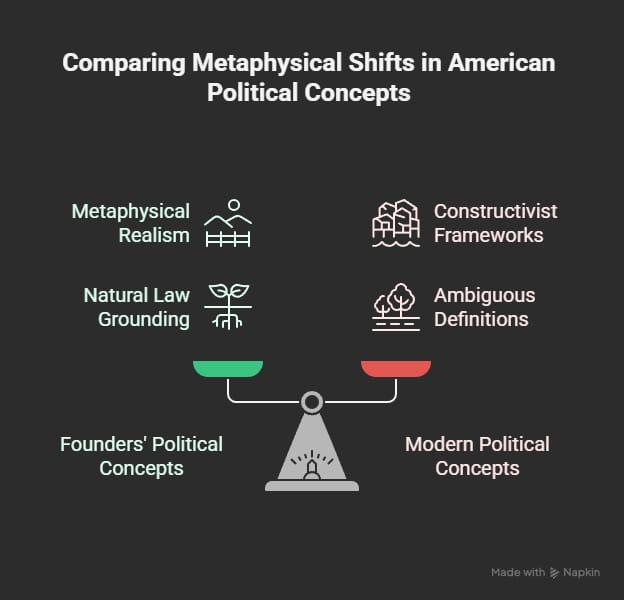

Over the past two centuries, many of the key terms central to American political life have undergone metaphysical and epistemic distortion. Where the Founders and their intellectual forebears grounded political concepts in metaphysical realism and natural law, modern usage often reflects constructivist, nominalist, or utilitarian frameworks. This semantic drift has rendered terms such as "rights," "equality," and "liberty" ambiguous or incoherent, which in turn destabilizes the civic order. A nation cannot sustain itself when its citizens no longer share the same definitions of its foundational principles (Wilson, 1790/1967).

The result of continuous metaphysical and epistemic warfare

This paper presents the beginnings of a realist lexicon—a map of the original definitions of key American concepts. Each term is rooted in ontological and theological assumptions present at the American founding. These original definitions are contrasted with modern distortions, which tend to sever political language from metaphysical and moral reality.

The Realist Lexicon

Term | Realist Definition | Modern Distortion |

|---|---|---|

Covenant | A morally binding agreement under divine witness, forming the foundation of the American polity and rooted in shared obligations and enduring moral duties. Covenants were seen as framing both civil society and political constitutions, particularly in Puritan and early state contexts (Massachusetts Constitution, 1780). | A religious or historical curiosity, often dismissed as irrelevant to secular politics or misunderstood as merely symbolic. |

Democracy | A form of direct popular rule that, according to most Founders, posed a threat to ordered liberty and republican governance. Democracy was often associated with mob rule and the erosion of property rights and virtue (Adams, 1787/1850; Madison, Federalist No. 10). | An idealized system of governance where popular will is considered supreme, often conflated with constitutionalism and used to justify majoritarian absolutism. |

Equality | Equal moral worth and legal standing under God and law, allowing for natural distinctions in ability and station (Adams, 1787/1850). Note that this does not mean equality in capability, propensity, or identity. | Forced sameness in outcome, behavior, or status regardless of nature or merit, often extended into the concept of equity. |

Justice | The moral virtue of rendering to each his due, in accordance with natural law (Aquinas, ST II-II, Q.58). Natural law does not change, and neither does what is just. | Redistribution based on perceived inequality or social grievance, perpetually updated in accordance with the mores of the day. |

Law | An ordinance of reason for the common good, made by one who has care of the community, and promulgated (Aquinas, ST I-II, Q.90). If a law contradicts natural law, it isn't a law. | The will of the sovereign or administrative state, defined by procedural legitimacy or power rather than moral truth. Law is treated as an evolving policy tool without inherent relation to justice, grounded not in eternal order but in human authority and enforceability. |

Liberty | The power of acting according to the determination of one’s will (Reid, 1785/1997). Liberty in this view is not mere license, but the ability to act in accordance with reason and moral law. | Unrestricted individual autonomy, including license to violate moral law. |

Natural Law | The eternal, knowable order of creation by which human beings discern good and evil through reason (Aquinas, ST I-II, Q.91-94). Natural law arises from the rational nature of man, which is permanent and universal, as man rationally participates in the eternal law. | An outdated religious or subjective framework replaced by evolving social norms. |

Personhood | The ontological status of a rational, moral agent made in the image of God (Wilson, 1790/1967). | A legal designation based on function, sentience, or political classification. |

Reason | The faculty by which humans discern natural law and order their actions toward ends appropriate to their nature (Reid, 1785/1997). | A subjective tool of analysis, subordinate to emotion or social constructs. |

Religion | The virtue of rendering due worship to the Christian God, essential to civic order and the cultivation of virtue. In the American founding context, “religion” referred specifically to Christian doctrine and worship, particularly within Protestant traditions. It was not a generic category applicable to all spiritual systems, but a covenantal obligation grounded in Scripture and natural law (Aquinas, ST II-II, Q.81; Massachusetts Constitution, 1780). | A private belief system, wholly subjective and interchangeable across cultures, disconnected from public morality. Today, “religion” is often used as a broad category encompassing anything from deism to animism, thereby evacuating its public, covenantal, and theological specificity. |

Republic | A mixed (national and federal) constitutional order founded on rule of law, separation of powers, and moral virtue (Madison, Federalist No. 39). While not all republics are covenantal, the American republic was uniquely framed by a covenantal logic rooted in Protestant theology and classical legal tradition. | Any elected government, often used interchangeably with democracy. |

Rights | Inherent moral claims grounded in human nature and natural law, pre-political and immutable (Aquinas, ST I-II, Q.94). Since rights are inherent claims grounded in natural law, they originate from our place in the order of creation as laid out in natural law. In the founding era, "rights" and "natural rights" were synonymous; they were understood as moral claims derived from the Imago Dei, not created by governments. | Arbitrary entitlements granted by the state or based on group identity or utility. |

Truth | The correspondence of intellect to reality (Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1011b26). | A construct of power, perspective, social consensus, or whatever works at the time (as per the pragmatists). |

The Ontological and Epistemic Roots of American Governance

The American political order was not founded on contract alone, but on covenant—an oath-bound relationship among persons and with the divine. As articulated in early state constitutions, such as that of Massachusetts (1780) invoking God as the Great Legislator of the universe, political authority was understood as deriving from God and mediated through morally accountable persons. The anthropology assumed by the Founders was theological and realist: man was created in the Imago Dei (the image of God), fallen but rational, capable of moral knowledge, and in need of civil order to restrain vice and cultivate virtue (Federalist No. 51).

Unlike a contract—which is utilitarian and can be dissolved by mutual consent—a covenant binds the parties to a shared moral order and appeals to divine authority. For instance, after the biblical Flood, God makes a covenant with Noah, promising never again to destroy the world by water (King James Bible, 1769/2024, Genesis 9:8-17). This covenantal framework informed the self-understanding of early American communities and shaped their conception of lawful resistance, civic responsibility, and institutional legitimacy. While not all republics are covenantal, the American republic was uniquely framed by covenantal logic, blending classical forms with theological substance.

James Wilson, a signer of the Declaration and architect of the Constitution, rooted his legal philosophy in natural law, affirming that “law and liberty cannot rationally become the objects of our love, unless they first become the objects of our knowledge” (Wilson, 1790/1967, p. 626). He distinguished between the mutable commands of rulers and the immutable order discoverable by right reason.

The Anti-Realist Aftermath

The destruction of these metaphysical foundations can be traced to several philosophical shifts that were imposed on the American mind from various avenues of approach—intellectual, legal, educational, and ecclesial (to be discussed in later papers):

Nominalism: Denial of real universals in favor of linguistic conventions, severing language from nature.

Pragmatism: Redefining truth as utility or social consensus, as opposed to correspondence with reality.

Constructivism: Treating identities, norms, and values as human creations, not reflections of eternal order.

Progressivism: Embracing historical change as normative, rejecting fixed moral law in favor of evolving norms.

Epistemology (Severed from Metaphysics): The modern invention of epistemology as a branch distinct from metaphysics severed the pursuit of knowledge from questions of being, reducing knowledge to analysis of belief rather than participation in truth. This fragmentation fostered skepticism and rendered classical claims to truth and natural law increasingly unintelligible.

These movements collectively displaced the realist foundations of American governance and civic life. Where rights were once reflections of the divine order, they are now reduced to expressions of collective will imposed and revoked via government. Where law was once a rational ordinance rooted in the eternal, it is now an instrument of administrative power.

Conclusion: Language is the Battlefield

Political renewal in America requires more than policy reform; it demands the recovery of the language of reality. The American Founders spoke the language of realism: of truths that are self-evident because they correspond to nature and nature’s God. In stark contrast, modern discourse speaks in the language of construction, management, and force. By restoring the realist meanings of rights, law, liberty, and equality, we begin the effort to re-anchor our political and cultural institutions in the order of being.

This lexicon is a retrieval project—a metaphysical cartography of the American mind. To defend liberty and justice, we must first remember what they are.

References

Adams, J. (1787/1850). A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America (Vol. 1). Charles C. Little and James Brown.

Aquinas, T. (1265–1274/1947). Summa Theologica (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). Benziger Bros.

Aristotle. (350 B.C.E./1984). The Complete Works of Aristotle (J. Barnes, Ed.). Princeton University Press.

Federalist Papers. (1788/2001). In C. Rossiter (Ed.), The Federalist Papers (A. Hamilton, J. Madison, & J. Jay). Signet Classics.

Jefferson, T. (1776/1975). The Declaration of Independence. In M. Peterson (Ed.), Thomas Jefferson: Writings. Library of America.

Massachusetts Constitution. (1780). Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. National Constitution Center’s Historical Document Library. Retrieved June 18, 2025, from National Constitution Center website.

Reid, T. (1785/1997). Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (D. Brookes, Ed.). Pennsylvania State University Press.

Wilson, J. (1790/1967). Collected Works of James Wilson (K. Hall & M. Hall, Eds.). Belknap Press.